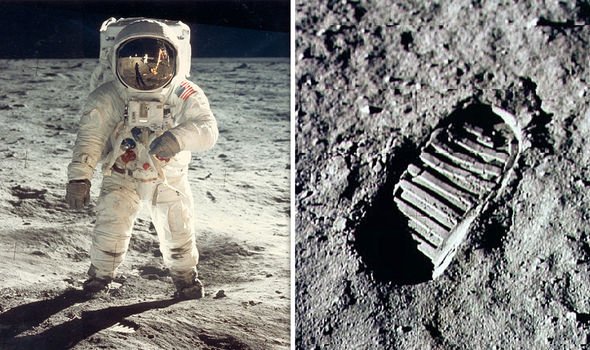

On July 16, 1969, astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins lifted off from Launch Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on a journey to the Moon and into history. Four days later, while Collins orbited the Moon in the command module, Armstrong and Aldrin landed Apollo 11’s lunar module, Eagle, on the Moon’s Sea of Tranquility, becoming the first humans to set foot on the lunar surface.

Neil Armstrong: “That’s one small step for a man; one giant leap for mankind.”

It was a day of miracles and wonders. That much I remember very clearly. One did not need the brainpower of a scientist or the erudition of a philosopher to know it. I was just an 8-year-old boy gazing through a bedroom window at a crescent moon, boggle-minded. People were up there.

July 20, 1969. The Internet reminds me that it was a Sunday, so there’s a nearly 100 percent chance that I started the day glumly preparing for church. All the parents were still married in those days, and most of the kids in our fecund suburb on the western edge of the Great Plains were passably compliant. Scrubbed and neat, we all would have been praying that morning for the astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins — who seemed to me the unluckiest man alive, doomed to circle just above the moon while his fortune-blessed comrades flew down to walk on its pockmarked surface.

That day and the days leading up to it were like a second Christmas. By that I mean they passed with excruciating slowness. It is said that people of a certain age all remember where they were when news came of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination. For my slightly younger cohort, Apollo 11 was that universal moment. But a shock leaves a more vivid, more jagged impression than the memory of a long-awaited culmination.

Thus, the waiting itself is among my clearest memories, one long day after another as Apollo 11 seemingly inched across space toward that impossibly distant, yet tantalizingly close, world. History itself became a tedious family road trip with an entire nation asking, “Are we there yet?” Willa Cather once wrote of crossing the prairie: “The only thing very noticeable about Nebraska was that it was still, all day long, Nebraska.” Even more true of space travel.

Recently, I asked my mother what she remembered of the day. Her answer was characteristic: She recalled her touchingly humane fear for the safety of the crew. I don’t think I gave that a moment’s thought. Little is more abstract to children than some distant adult in peril. My friends and I were wanton with our unconcern. The Vietnam War was raging, and my best friend’s father was over there. Yet our favorite games involved flying imaginary raids and combat in imaginary jungles. We died often, always recovering quickly.

While we were at church, Armstrong and Aldrin floated from the command module into the lander, leaving poor Collins behind. Another infinity dragged by as the little craft flew toward the moon. Years later, I learned that this trip was a nerve-jangling succession of blaring false alarms, a missed landing zone and a nearly spent fuel supply. At the time, we had only the laconic voices of the astronauts and Mission Control to shape our impressions, and they made the whole thing sound about as exciting as sweeping the garage. I went outside to kill time, popping occasionally into the den to check on their progress.

Blog EBE English Book Education

Blog EBE English Book Education