Tolkien’s grandson on how WW1 inspired The Lord of the Rings

For the 125th anniversary of his birth, Simon Tolkien describes how the Great War lives on in JRR Tolkien’s stories.

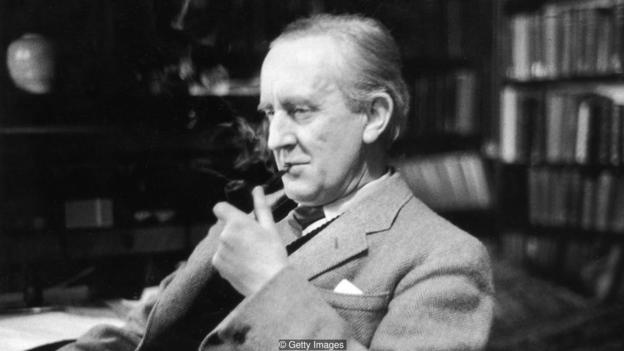

My grandfather, JRR Tolkien, died when I was 14. He remains vivid to me but through child-like impressions – velvet waistcoats and pipe smoke; word games played on rainy afternoons in the lounge of a seaside hotel or standing on the windy beach down below, skipping flat black pebbles out across the grey waves; a box of matches that he had thrown up in the air to amuse me, rising and falling as if in slow motion through the branches of a horse chestnut tree.

There was a clue here to his personality: an impressive confidence in his own opinions and a steely self-belief that had nothing to do with the avuncular, affectionate grandfather that I knew. I was too young of course to wonder then about how he reconciled the pantheistic world that he had created with his own fervent Christianity.

Later I came to realise that my grandfather was not just the author of The Lord of the Rings but also an intellectual giant, who spoke and read numerous languages and was a world-renowned expert in his chosen field. My father has devoted himself tirelessly to editing my grandfather’s unpublished writing for publication in the 43 years since his death and this has so far run to more than 20 books.

Mining memories

As a man, I felt dwarfed: how could I not? And in my own middle age spurred me on to have something of my own to know myself by; to become a writer myself. This wasn’t easy. I thought my first book was a masterpiece, but the unanimous negative reaction of numerous literary agents on both sides of the Atlantic soon convinced me of my error! But I persisted and slowly found some measure of success. I had thought of my grandfather as an obstacle; he had become the great tree casting the long shadow from which I wanted to escape. Was I to be Simon Tolkien or just the grandson of a great man?

Somewhat ironically, I soon found that I needed my grandfather to sell my books. Writers cannot succeed without publicity, and my name was my passport to gaining media attention. Interviewers understandably wanted to know what it was like to be JRR Tolkien’s grandson and so I mined my memories until they became stale: gold turned to dust in my hand.

I had always wanted to write about World War One. In the small English villages where I grew up the war memorials were engraved with long lists of men who had never come back from the trenches. They had left their homes for the first time in 1914, singing as they marched away towards the great adventure, only to find hell on the other side of the English Channel. Warfare had changed forever in the 100 years since Waterloo. Killing had become an industrial process and flesh and blood could not match high explosive shells and machine gun bullets.

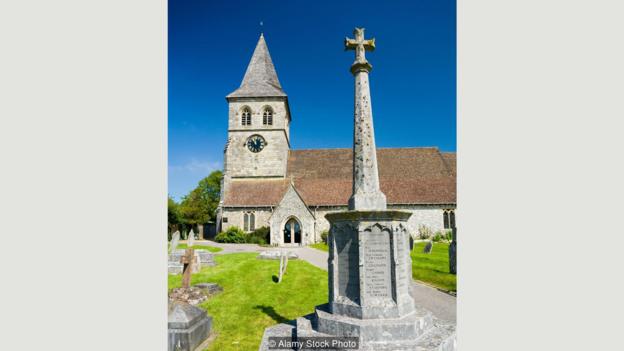

The soldiers waited for death in mud-filled holes in the ground, terrified of the day when they would be ordered over the top. So many died wretched anonymous deaths in no man’s land, bleeding away, parched by an intolerable thirst. I saw their young faces in old sepia-tinted Edwardian photographs: innocent with no awareness of the horrors that lay ahead, and I wanted to try to bring their experience to life. But for a long time, I did not feel ready; I was daunted by the size of the undertaking.

‘Industrialised evil’

Finally, I began. And as the chapters unfolded, I thought more and more of my grandfather, who had also fought in the Battle of the Somme. I had a photograph of him too: handsome and resolute in his officer’s uniform, with an unfamiliar moustache. If he hadn’t survived I wouldn’t exist. I wished that I had known him for longer so that I might have asked him about his experience. He had left no written record and, like many veterans, he had apparently rarely spoken of his ordeal.

But then I went back to The Lord of the Rings and realised how much his grand conception had to have been informed by the horrors of the trenches. Evil in Middle Earth is above all industrialised. Sauron’s orcs are brutalised workers; Saruman has ‘a mind of metal and wheels’; and the desolate moonscapes of Mordor and Isengard are eerily reminiscent of the no man’s land of 1916.

The companionship between Frodo and Sam in the latter stages of their quest echoes the deep bonds between the British soldiers forged in the face of overwhelming adversity. They all share the quality of courage which is valued above all other virtues in The Lord of the Rings. And then, when the war is over, Frodo shares the fate of so many veterans who remain scarred by invisible wounds when they return home, pale shadows of the people that they once were.

There is a sense too that the world has been fundamentally changed by Sauron even though he has been defeated. Innocence and magic are disappearing from Middle Earth as the elves leave, departing into the West. And I think that my grandfather must have felt the same about Europe in the aftermath of the Great War: how terrible it must have been to fight ‘the war to end all wars’ only to have to send your sons to fight in another war 20 years later.

In my book, No Man’s Land, I wrote about an orphan, Adam who, like my grandfather, won a scholarship to Oxford and fell in love, but then had to leave his hopes and his beloved behind to go to France, knowing that he would be unlikely to return. Adam is changed forever by his experience just as my grandfather was, and in telling his story, I feel that I have forged a bond with my grandfather and honoured his memory; by following in his footsteps, I can finally come out of his shadow.

Simon Tolkien is the author of No Man’s Land, which is inspired by the real-life experiences of his grandfather, JRR Tolkien, during World War One (Doubleday/Nan A Talese, on sale January 2017. Published by HarperCollins in the UK).

Blog EBE English Book Education

Blog EBE English Book Education